Implementation Description

Like most schools during the COVID-19 pandemic, Community Public Charter School (CPCS) was faced with both an urgent need for more technology and a sudden abundance of options for virtual learning applications.

During the 2020-21 school year, CPCS operated on a hybrid model (with groups of students alternating between virtual and in-person learning days) until October when they transitioned to in-person learning five days per week. In fall of 2020, CPCS only had 75 Chromebooks for 210 students, and some of their families lacked reliable internet at home. The school’s administration quickly realized that this was “an immediate need that needed to be addressed” in order for virtual learning to be a success (M. Dellinger, personal interview, March 24, 2021). All families were asked to provide information about their technology and internet needs, which began to lay the groundwork for one-to-one accessibility for all – a significant step towards addressing technological inequity at the school (Anderson, 2019). Every student received a school-provided computer and a copy of the computer loan policy which outlined the school’s expectations for properly maintaining the equipment. By spring 2021, a minimum of 323 laptops were checked out by students on a daily basis. Two families also were provided with internet hot spots. This access to technology and the internet would not have been possible without the support of NC ACCESS grant funds.

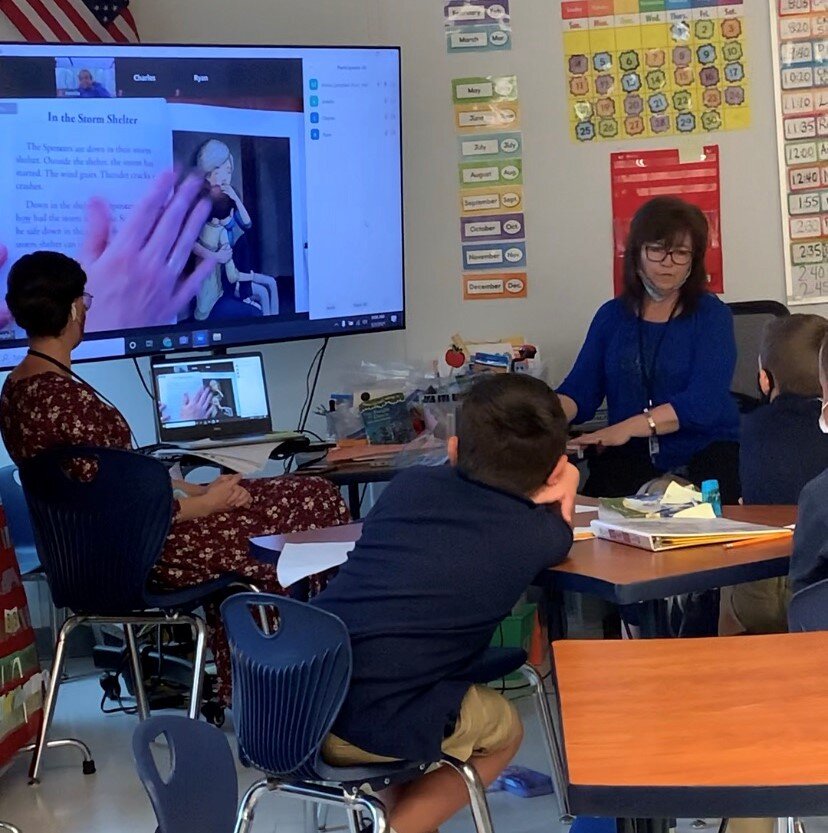

In October when the school was able to fully transition to in-person instruction, approximately 40 students, which represents about 12% of the student body, chose to continue learning virtually for the remainder of the 2020-21 academic year. For those students, 65-inch televisions were installed in classrooms allowing in-person learners and virtual learners to synchronously interact with each other and their teachers in real-time.

Having the available technology made virtual learning much more feasible. But as so many virtual learning tools became available for students during COVID-19, families and teachers alike soon felt overwhelmed trying to keep up with all of the different applications and login information they were using every day. CPCS staff decided that everything needed to be streamlined. As such, CPCS organized all of the necessary links students and their families need into one easy-to-access portal, Parent Square, requiring only one username and password per child. There are a number of similar products on the market, and you can learn more about why this platform was selected over other options by contacting the school.

Use of a centralized communication tool allowed families and school staff to more easily support student learning. Once the student or parent has logged into the portal, they are able to access all the links they need for things like yearbook information, the school’s hot lunch program, daily classwork, and more. With the sudden availability of new technology tools to support teaching and learning in a virtual environment, CPCS recognized the need to train parents and students on how to utilize these tools successfully. In order to do so, the school designated the first two weeks of the 2020-21 academic year for introducing their students and their families to the technology they would be using throughout the school year. Step-by-step instructions were provided and families were shown which icons to look for in order to access the internet, their class’ webpage, and student’s email. This was a largely teacher-led initiative because they recognized that the learning environment would be negatively impacted due to a lack of understanding on how to use the learning resources effectively. CPCS also hosted in-person parent orientations with no more than five families at a time, due to crowd size restrictions, in which they shared video recordings that described how to use the school’s selected technology platforms. The use of pre-recorded videos ensured consistency each time it was shared with a different set of parents. The information provided during the parent orientations increased parents’ ability to support their child(ren) during remote learning and helped them feel more included and involved in their child(ren)’s education in general. Kathleen Cotton and Karen Reed Wikelund of the Office of Educational Research and Improvement (1989) found that “providing orientation and training enhances the effectiveness of parent involvement. Research in this area indicates that parents generally want and need direction to participate with maximum effectiveness” (p. 3). And, as a 2013 study showed, “family involvement is positively linked to children’s outcomes in preschool, kindergarten, and the early elementary grades. A preponderance of research confirms the link between family involvement and children’s literacy skills...math skills...and social-emotional skills” (Van Voorhis, Maier, Epstein, & Lloyd, 2013, p. 75). CPCS was committed to ensuring that the entire family was prepared to provide the best virtual learning experience possible for all students.

Results

When virtual learning began during the spring of 2020, CPCS staff was checking in with families regularly, especially when students were not attending classes, in an effort to learn of any technical issues that might be preventing them from actively engaging with their lessons. Now that technology is no longer a barrier for most CPCS families, teachers only have to regularly check on a very limited number of families to monitor and address persistent technological needs.

As learners are more engaged, achievement scores have also gone up. For instance, according to CPCS’ North Carolina Check-Ins the number of third-grade students proficient in math has increased from 39.6% in the fall to 50.4% in the 3rd quarter. Furthermore, the number of students proficient in reading has increased from 62.3% in the fall to 71.2% in the 3rd quarter.

Undoubtedly the best result of all is the fact that the educationally disadvantaged families at CPCS feel seen and cared for, and that has led to an increased ED enrollment at the school. CPCS set a goal of 35% ED student population for 2020-21 school year and exceeded their goal by enrolling 36%. They anticipate at least 38% ED students in 2021-22. In reference to the enrollment increases seen at the school, Monica Dellinger, CPCS Assistant Principal, noted that “the two major selling points- unbeknownst to us- were the fact that we became a one-to-one device school and provided that to everybody...and anyone that needed internet access we provided that as well...So I think being able to provide for the students’ immediate needs- both socially and educationally- that has been a selling point with our current families, so they have been able to talk about their successes in the community, and that’s definitely increased enrollment” (personal interview, March 24, 2021).

Challenges

Even after CPCS consolidated every application into one easy-to-use portal, students still had trouble remembering what their individual passwords were. This problem was exacerbated by the fact that students created their passwords at home, meaning teachers were unaware of students’ passwords and therefore unable to assist in the login process. Without being able to login, students could miss out on instructional time and assignments. In 2021-22 CPCS plans to have students use a classroom-specific password so that it’s easier for students and teachers to remember and access all school related materials and information.

Future Modifications

Now that students understand the technology and have found a learning rhythm, CPCS plans to build on the individualized instruction they delivered during the 2020-21 academic year. They will provide more designated time for small group learning, daily WIN (What I Need) sessions, and increase their use of the STAR Reading and Math program-collected data to better target instruction based on the needs of each student.

Critical Components

Getting Started

The main factor that contributed to the success of the one-to-one technology program was the communication with families ahead of time. School staff members were able to discover who specifically needed computers and internet access.

The school also provided families with instructional videos to help them feel more equipped to use the laptops.

CPCS set the expectations for what acceptable computer care would look like with a signed agreement for families.

It was also absolutely imperative that the teachers and staff dedicate the first two weeks of instructional time to teaching the kids and parents how to use the new technology.

Ongoing Supports

The use of one communication tool containing links to all apps has been instrumental in ensuring that everyone can easily utilize and access all resources essential to student learning. Use of this tool will continue to be a critical component of the success of this strategy.

CPCS will continue to provide instruction to both parents and students as they learn to navigate the applications necessary to access all school-related information and lessons.

Equity Connections

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic families who did not have access to the internet or electronic devices at home faced a barrier regarding equity of education (Anderson, 2019). CPCS offered laptops and internet access to anyone in their school family who needed it. Providing this kind of support and resources to educationally disadvantaged students is likely to shorten the achievement gap in school, and it may also have long-term implications for student success after graduation (Lynch, 2017).

Much like the uniforms students wear at CPCS, school-provided laptops serve as an equalizer (Perez, 2018). There is no distinction between rich and poor when everybody’s computer looks the same and comes from the same place.

The parent orientation events that CPCS hosted increased family involvement, which is a key factor in ensuring the success of any student, including those facing educational disadvantages. As pointed out in Karen Bogenschneider and Carol Johnson’s 2004 study, “the last 15 years of school reform have focused on course curriculum, instructional methods, and teacher training. Yet these reforms have not accomplished as much as they might because academic achievement is shaped more by children’s lives outside the school walls, particularly their parents” (Bogenschneider & Johnsons, 2004, p. 1). CPCS staff sought to inform families through orientations so that parents would be equipped for increased involvement in their children’s education.

Research

1. Anderson, K. (April 29, 2019) How Access to Technology Can Create Equity In Schools. Digital Promise. Accessed on April 8, 2021. Retrieved from https://digitalpromise.org/2019/04/29/equity-in-schools-access-technology/

2. Bogenschneider, K. & Johnson, C. Family Involvement in Education: How Important Is It? What Can Legislators Do? University of Wisconsin-Madison University Extension. Policy Institute for Family Impact Seminars. P. 1. Accessed on April 13, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.purdue.edu/hhs/hdfs/fii/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/fia_brchapter_20c02.pdf

3. Cotton, K. & Wikelund, K. R. Parent Involvement in Education. School Improvement Research Series: Close-Up #6. P. 3. Accessed on April 13, 2021. Retrieved from https://educationnorthwest.org/sites/default/files/parent-involvement-in-education.pdf

4. Lynch, Matthew. (March 31, 2017). The Absence of Internet at Home is a Problem for Some Students. The Advocate. Accessed on April 8, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.theedadvocate.org/the-absence-of-internet-at-home-is-a-problem-for-some-students/

5. Perez, Talia Klein. (2018) The Perspective on School Uniforms. The Perspective. Accessed on April 8, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.theperspective.com/debates/living/perspective-school-uniforms/

6. Van Voorhis, F.L., Maier, M. F., Epstein, J. L., & Lloyd, C. M. (October 2013). The Impact of Family Involvement on the Education of Children Ages 3 to 8: A Focus on Literacy and Math Achievement Outcomes and Social-Emotional Skills. MDRC. P. 75. Accessed on April 13, 2021. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED545474.pdf

7. United States Census Bureau, Quick Facts North Carolina, Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NC/PST045219

Click on the links below to learn more about this school and to download the complete Best Practice Implementation Strategy.